Coronavirus: The desperate dilemma at the heart of the COVID-19 outbreak

Sky's economics editor Ed Conway sees COVID-19 threatening the way the world does business in the long term.

Monday 2 March 2020 15:26, UK

Here is the desperate dilemma at the heart of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Solving the outbreak and saving people's lives means inflicting damage on your economy - economic damage that could also harm people's lives.

Confining people at home, shutting down workplaces and schools, encouraging people not to go out to pubs and restaurants and shopping malls: it is a surefire way to dampen both supply and demand of activity.

So while containment might well help address one crisis, it provokes another one altogether: an economic crisis where people potentially run short of money and face worse life outcomes as a direct result.

It is worth bearing this in mind when considering the impact of the outbreak.

Of course: lives being lost and people's health being at risk is the primary worry here.

But the economic knock-on consequences are just as real. And, ironically enough, when it comes to the economic toll the behaviour of healthy people could cause as much, if not more, economic damage than the behaviour of those who are infected with the disease.

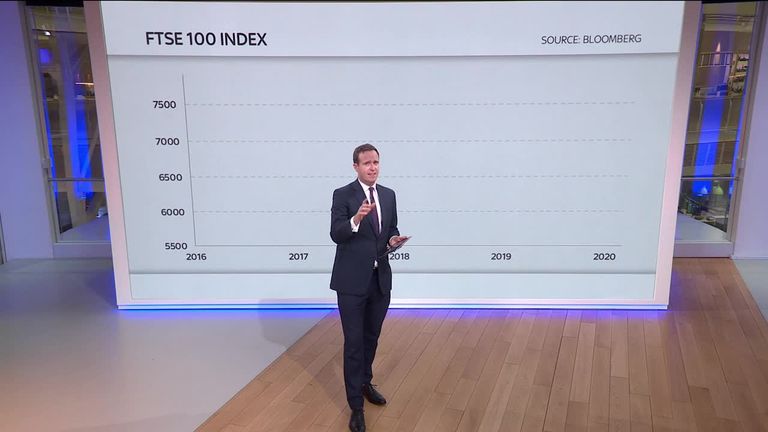

This is why the outbreak has caused the biggest weekly dent on share prices since the financial crisis.

It is why, today, the Paris-based OECD has slashed its forecasts for global (and for that matter UK) economic growth.

And there was an ominous nuance buried in the OECD's forecasts.

When their Economic Outlook was sent to the publishers last week the central set of forecasts was described as their "base case".

On Monday, the OECD is describing those central forecasts as a "best case scenario". That is how fast this is moving.

What does that "best case" look like? Well for one thing, the UK's nascent economic recovery is over.

The OECD was planning to upgrade UK growth until coronavirus came along.

Now it expects this country's economy to grow by only 0.8% this year - the weakest since the financial crisis.

The rest of the world is similarly affected: nearly every country in the world saw its growth forecasts slashed.

One or two countries had unchanged forecasts - but this was primarily Southern Hemisphere nations which, as of yet, haven't had major outbreaks and haven't had to impose containment measures.

Again: it's the containment measures that cause most of the economic damage.

Damage to tourism; to computer and electronic equipment manufacturers as they shut down factories; to car factories doing likewise, either because their workers are at risk or because the parts they rely on are no longer arriving from elsewhere; to the pharmaceutical sector; to the entertainment and leisure sector, where activity is expected to plummet as concerts and events are cancelled; to education; to everything, says the OECD's chief economist Laurence Boone, "with collective meetings".

The OECD also published what they called a "domino scenario" and it's considerably more scary.

It entails recessions across almost all of Europe, including the UK. It implies a global slump that gets close to what we saw in the financial crisis. And this is not even their worst-case scenario since it still assumes most of the Southern Hemisphere escapes unaffected.

And here is the awkward thing: much of the ammunition used by policymakers during the financial crisis is already spent.

Interest rates are still near rock bottom in many economies, including the UK. Even if central bankers cut rates, it's not altogether clear that would make all that much difference. And were governments to step in with tax cuts, that might help a bit - but not necessarily.

There are some obvious areas where governments can spend a bit of money: on health facilities, on testing and on ensuring everyone who gets infected with COVID-19 can have the best available treatment.

But beyond this, what's actually most needed is not money but time.

Households who aren't able to work because of the outbreak will need time and forbearance from their mortgage, energy and food bills.

Businesses unable to produce will need time to get back up and running without facing unnecessary tax bills.

Expect a lot of special measures such as the above in Rishi Sunak's first Budget next week, which will be far more focused on coronavirus than is currently expected.

The good news is that even following a severe outbreak, the damage should only last months rather than years, and that much of it should bounce back afterwards.

But there is a more extreme scenario, in which COVID-19 proves to be the final nail in the coffin for the current era of hyperglobalisation.

Globalisation - whereby the world is interconnected at various levels - is already under threat.

From Donald Trump, who uses tariffs as a tool of economic diplomacy; from Brexit which will involve the erection of trade barriers between Britain and Europe; from the rise of national movements which rail against "citizens of the world".

Now comes the coronavirus, itself an agent of deglobalisation, forcing companies to localise their supply chains (because those in China and other countries are themselves shut down), forcing tourists to stay home and preventing workers from doing business travel, forcing people to reconsider whether "just in time" manufacturing, whereby you rely on parts to be delivered minutes before you assemble them into a product, is really the best way to run their businesses.

This is more than a trivial concern.

The world's collective economic model relies on the relatively free movement of goods and people from one place to another.

Yet this model is under threat at every turn - you only need look at the scenes on Greece's border with Turkey for further vivid examples.

COVID-19 has the potential to accelerate this process, with far more lasting effects for the way we live our lives today.